Independent Assessor of Complaints for the Crown Prosecution Service: Annual Report 2023-24

July 2024

Independent Assessor of Complaints for the Crown Prosecution Service: Annual Report 2023-24

1. About the IAC Service

The Independent Assessor of Complaints (IAC) for the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) is completely independent of the CPS, providing an impartial service that complainants can have confidence in.

The IAC role is to:

- Investigate service complaints about the CPS following conclusion of its internal complaints process (known as Stage 1 and Stage 2).

- Look at whether the CPS properly followed the Victims’ Code guidance on the services that must be provided to victims.

- Check that the CPS has followed its complaints procedure.

- Check that the CPS followed its own policies, procedures and guidance.

The IAC’s aim is to:

- right wrongs for complainants where possible and proportionate.

- drive improvements in the CPS to reduce the likelihood of similar service complaints arising in the future.

Anyone who has complained to the CPS and remains dissatisfied with the outcome of their service complaint at the end of Stage 2, can escalate the matter to the IAC and request an independent review. Service complaints include, for example: the conduct of CPS staff, such as rudeness or being given incorrect information; poor communication; and service standards such as breaches of its own policy, or of the Victims’ Code.

Legal complaints – such as how the CPS applied the Code for Crown Prosecutors in deciding whether to prosecute; or decisions about witnesses to call at a trial or evidence to be relied upon – cannot be reviewed by the IAC. These are legal decisions that are rightly reserved for independent prosecution lawyers.

Most complaints the IAC investigates comprise both service and legal elements. Sometimes the complainant’s central concern is legal, and any service element may be minor. My terms of reference allow me to reject such complaints where I am satisfied that the CPS has dealt appropriately with the service aspects of the complaint, or where any service element is so minor as to be disproportionate to investigate.

Terms of Reference

The IAC’s terms of reference (ToR) set out how I work, my relationship with the CPS, and the limits of my jurisdiction. I review them annually, in conjunction with the CPS, and any proposed amendments are brought to the independent CPS Board for approval.

They were amended this reporting year, in May 2023, to incorporate my new ability to make ‘IAC referrals’, (although that change was actually agreed by the Board the previous year). The IAC referral process was introduced to mitigate changes to my ToR implemented in November 2022, which had removed my specific authority to recommend compensation for complainants who had lost money as a direct result of CPS actions. You can read more about IAC referrals and the adverse impact of the November 2022 change in the next section.

As I have just months ahead of me as IAC, I have not suggested any amendments this year because any changes I would have recommended (see below) would be very significant and I need to be mindful that my successor might wish to take a different approach. I have, though, as flagged up last year, now discussed with the CPS making changes to service standards and deadlines. The principle has been agreed that the 40 working days target has never been realistic (the IAC target is significantly more challenging than most other independent adjudicators). This is still work in progress and it will be beneficial to involve my eventual successor in that, as it will impact them (albeit in a positive way). It is a necessary change, to ensure that published timescales represent the reality of the wait for complainants to have their cases reviewed. Both the IAC and the CPS should be working to realistic timescales when responding to escalated complaints.

I have also had a preliminary discussion with the CPS on the need to improve governance around what happens on the rare occasions when an IAC recommendation is not accepted. Although I believe that there is already clarity, the case of Mr A during the year – which you can read about in this report – highlighted that improvements could be made. Again, I hope that my successor can be involved in this, and any resultant changes to the IAC’s ToR.

When reviewing my ToR this year, I would have liked to revisit the removal of my ability to recommend compensation, in light of the impact this has had during the year (which you can read about below), but I have decided to leave that to my successor to take forward if considered necessary. I am hopeful that my discussions with the CPS in 2024 on revising the goodwill payments policy may help to address some of my concerns.

You can find the current IAC’s terms of reference (ToR) at the end of this report and online at www.cps.gov.uk/independent-assessor-complaints

Moi Ali, July 2024

2. The Year’s Key Events

This is my final report as IAC: I complete my second term of office at the end of October 2024. I am pleased to have been consulted on updating the job description to better reflect the changes to the role over the last six years, although disappointed that there will be limited overlap between outgoing and incoming IAC. My taking up the role six months before my predecessor stepped down was valuable to both of us, and a good opportunity to work together to clear the backlog.

This is an opportune time to look back over my time as IAC and to reflect. When I took up the role in 2018, HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate (HMCPSI) had just reported on the quality of CPS complaints responses at Stages 1 and 2, and in particular the lack of empathy in many of the examples scrutinised. The report made difficult reading for the CPS. I was asked if there was anything I could do to help, and amongst other things, I designed a practical workshop which I took out on the road to a number of CPS areas. It looked specifically at how to write in a more empathetic way. When the Inspectorate returned to the CPS last year, I was happy to give them my take on CPS letters: there had been a big improvement, and many of the letters I review are excellent. Where I see a particularly good (or bad) letter, I now feed this back to the writer. Sometimes, CPS lawyers feel empathy and concern for the complainant, but struggle to convey this sentiment while also maintaining appropriate professional boundaries. It is a difficult balance, but the CPS has invested in training for staff involved in letter-writing, and that investment has paid off.

One of the most disappointing reflections over the last two years is the erosion of my ability to give a fair remedy to complainants at the independent review stage. The current situation at the CPS is inherently unfair to complainants, out of kilter with many other public bodies, and does not accord with PHSO best practice guidance (see Principles for Remedy | Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO)).

In last year’s report, I gave an update on my 2019 recommendation that the CPS consider a more complainant-friendly policy of “payments to put things right”.

Progress on responding to the recommendation had been painfully slow and unfortunately, as I reported last year, the eventual response was to amend my terms of reference to remove my ability to recommend compensation for actual financial loss and then to amend the CPS Goodwill Payments policy. Although that policy provides for a “modest financial payment” at any stage, the CPS has never been able to award compensation for direct or indirect financial loss at Stages 1 or 2 of the complaints process, even where it accepts that it has caused someone to lose money. Since November 2022, however, I have been unable to remedy the injustice of the CPS’s inability to initiate a compensatory payment for actual financial loss at the independent review stage. Far from my 2019 recommendation achieving a fairer process for complainants, it has become less fair. You can read more about the adverse impact of this change during 2023/24 below.

Consolatory Payments and Compensation

PHSO guidance states that “financial compensation for direct or indirect financial loss” may be an appropriate response for upheld complaints, but the CPS ‘Goodwill Payments Guidance’ published in May 2023 makes no provision for cases where “CPS actions resulted in identifiable financial loss” (other than litigation). The removal of my ability to remedy this leaves civil legal action as the only recourse available to complainants left out of pocket as a result of CPS actions.

In 2019 I recommended a simplified system: instead, the CPS has created a complex landscape. A complainant may qualify for a goodwill payment for the distress caused by a proven financial loss that the CPS accepts it caused, but not if they intend to pursue the actual financial loss. In such cases, no goodwill payment is available at Stages 1 or 2. The only way to potentially obtain compensation for proven financial loss is to begin legal proceedings against the CPS – a costly and daunting process, and not viable in most cases given the relatively small sums involved. In such cases, as no goodwill payment will be made for distress caused by the financial loss, the CPS has created an even bigger disincentive for complainants to pursue a just outcome.

Furthermore, I can recommend a goodwill payment at the independent stage, even if the complainant indicates that they may litigate. This is needlessly complex, inconsistent, and unfair. The complaints system should deal with complaints fairly, and on their merit, regardless of any legal action a complainant may be considering. Such an approach would likely avert rather than encourage litigation.

I am pleased that in 2024/25 the Goodwill Payments Guidance will be further revised, and I will again offer feedback to help make this as fair as possible. The CPS may not legally have a duty of care to victims for its errors, but morally it should. If they suffer financially as a direct result of CPS errors or omissions, this should be rectified. That is certainly the expectation of the PHSO.

‘IAC referrals’

My Terms of Reference changed this year to include an “IAC referral” to the Civil Litigation Team (CLT), and I made my first – and to date my only – referral. I will report on that case later in this report.

This new IAC referral process is a clunky and unsatisfactory workaround to help mitigate the negative impact of the removal of my ability to recommend compensation to which I believe a complainant is entitled. When I became IAC, I could ask the CPS to consider “making a compensatory or modest consolatory payment where there is clear evidence of uninsured material loss or severe distress caused by maladministration or poor service by the CPS”. Although the amounts I recommended were small (totalling just over £3,000 in 2019/20 across four cases), it was a useful mechanism for righting wrongs.

The CLT treat an IAC referral in a similar way to a ‘letter before claim’, so a complainant does not need to go to the effort and expense of engaging a solicitor. They will consider the legal basis of a case for compensation, and respond directly to the complainant with a no-fault offer, or reasons why no payment will be made. On the face of it, this appears to be a good way to deal with the issue – but it is not. In the one case referred, that of Mr A, the CLT took a defensive approach. This is not a criticism: it is their job to defend the CPS. Previously, however, I could apply the PHSO’s principles of fair remedy where there was evidence of financial loss from CPS actions or omissions. That is no longer possible and I can only offer a ‘goodwill’ payment in line with the CPS guidance.

Recommendations Rejected

My recommendations are just that: recommendations. They carry no weight, and I have no power or authority to compel the CPS to do anything. The CPS can reject an IAC recommendation, although it is unusual for that to happen. This year one recommendation was rejected, bringing to two the total number rejected over the last six years. It concerned Mr A.

When a recommendation is rejected, my ToR specify that the CPS must write to the complainant and to me, setting out the reasons, and I must report on these in my annual report and highlight such cases to the CPS Board.

Mr A’s Case

Mr A was assaulted by a stranger and left with permanently blurred vision and damaged teeth. His assailant was charged by police with common assault. Mr A told the CPS that the charge was insufficient to reflect his injuries.

The prosecutor in court concluded that it should be a more serious charge of assault occasioning actual bodily harm (known as ABH). The CPS wrote to Mr A about the amended charge after the hearing, but this letter crossed in the post with one from Mr A’s solicitors asking that the charge be increased to ABH.

The defendant pleaded guilty and the CPS shared Mr A’s Victim Personal Statement (VPS), receipts from his dentist and optician, and loss of earnings totalling over £650 with the court. At the sentencing hearing in a different court, these were not shared with the court or the prosecution barrister – and there was no application for compensation when the defendant was sentenced.

Mr A complained to the CPS but the deadline for responding to him kept being extended and he had to chase. The CPS accepted serious failings and offered the maximum goodwill payment of £500, but did not tell Mr A that the failure to provide the VPS was a breach of the Victims’ Code (allowing this part of the complaint to be escalated to the PHSO) or explain that he could escalate to the next stage of the CPS complaints process. Furthermore, there was no disclosure of further errors:

- the failure to prepare a Crown Court bundle, an advocate bundle, and instructions for the advocate (some of this was alluded to, but not in explicit terms).

- the failure to upload CCTV evidence to the court, and to provide this to Counsel and the defence only on the morning of the hearing.

Mr A wrote to me dissatisfied with the payment. With solicitors’ fees, his losses came to almost £1200. (He said that he had used solicitors to gather the information to justify increasing the charge to ABH.)

My office asked the CPS to escalate the complaint to Stage 2. The Stage 2 reply accepted that it was likely (but not certain) that the court would have awarded compensation. In response to the £500 offer, Mr A said he was: “not asking for too much or being greedy I just want what I would’ve received had the proper process been followed...”

I partly upheld the complaint. In addition to the two service errors admitted at stages 1 and 2 (failure to ask for compensation, and to read Mr A’s VPS at sentencing), was the failure to prepare the case for sentencing (and not openly admitting this when he complained); and the failure to upload CCTV and provide this to Counsel and the defence until the morning of the hearing (also not brought to Mr A’s attention).

Furthermore, the complaints handling was poor. Although efforts were made behind the scenes to resolve matters, the impression was that the complaint was not being addressed, and it took a long time for him to get any response.

The CPS accepted that Mr A had suffered uninsured material loss of £653 when offering a goodwill payment for not applying for compensation “when we should have been in a position to do so” which “led to the loss of the possibility of the court awarding compensation…” The CPS told Mr A that the payment of £500 was “in recognition of the service failure identified and the financial loss you sustained as a result of the defendant’s action [my emphasis].” Although he incurred cost and lost income as a direct result of the defendant’s action, CPS inaction/error denied Mr A the opportunity to be rightly reimbursed by the defendant. It is not for the CPS to recompense victims for defendants’ actions: only for its own service failures, and their consequences.

The CPS was in breach of its own Prosecutors' Pledge (on conviction, a prosecutor pledges to “apply for appropriate order for compensation…”). Mr A completed all the necessary paperwork for compensation and provided receipts. He did everything required, but the CPS let him down. I found it unreasonable to expect the innocent victim to suffer financially as a direct result of an organisation’s admitted failures.

While there was no guarantee that the court would have awarded the full amount of the claim, the CPS’s error denied Mr A the opportunity to ask, and the CPS conceded that an award was likely.

It is highly unusual for me to suggest a higher amount when the CPS has already offered a goodwill payment, especially as in this case when the amount was the maximum that can be offered under the Goodwill Payment guidance (without seeking Treasury approval). Taking all the factors into account though – the stress and inconvenience of having to raise a complaint and pursue two further escalations; the Victims’ Code breach; the Prosecutors' Pledge breach; the CPS’s poor complaints handling; and the further service failures, including not sharing CCTV evidence until the day of sentencing – I exceptionally recommended in these circumstances a small additional goodwill payment of £250. Previously I would also have recommended compensation for some or all of his actual financial losses, but of course, I can no longer do that and can only refer such cases to the CLT.

The CPS told me it rejected my recommendation on the basis that what happened to Mr A was not sufficiently exceptional to exceed the ‘maximum’ amount for a goodwill payment as set out in the published policy. (£500 is, in fact, not the maximum – see below). That these kinds of multiple service failures are not regarded as sufficiently exceptional should be a concern to the CPS. The CPS gave a different reason to the complainant.

Writing to Mr A

When a recommendation is rejected, my ToR are clear: the CPS must write to the complainant and to the IAC setting out why. The CPS did not write to me (although I was sent a copy of the letter that a senior member of staff sent to Mr A) in which Mr A was told that my recommendation: “exceeds the maximum payment I can offer. The IAC should not have offered you more than the maximum payment under our guidance and I apologise for the frustration that this may cause… Paragraph 5 of the Policy states that goodwill payments may be made up to £500. I agree that you are entitled to the maximum that the CPS can offer. However, as any payment made by the CPS would be payable out of public money, I am not permitted to make a payment which would contravene the Policy. This is the reason I cannot accept the IAC’s recommendation.”

The CPS misinformed Mr A: the policy says: “Goodwill payments will be made in accordance with HM Treasury’s guidance on managing public money. As part of the CPS’ delegated financial responsibility, a modest payment can be made under this guidance. In the event that payment exceeding our delegated authority is to be made [my emphasis], authorisation must be sought in advance from the Treasury, via the CPS Chief Finance Officer.” The policy is clear: the maximum is £500 without Treasury approval, but a payment exceeding that can be made with Treasury approval.

The senior staff member who wrote the letter also misinformed the Board, stating: “Our policy does not make any exception to [payments greater than £500]; those are the parameters in which the IAC must operate.” He omitted the line in the policy about the process for seeking Treasury authorisation to potentially enable payments that exceed the CPS’s delegated authority.

The CPS could, in any case, agree an IAC exemption with the Treasury. Some of my counterparts, such as the Independent Complaints Examiner at the Department for Work and Pensions, have such an exemption and can make decisions on payments up to £1,000. HM Treasury guidance states that its “approval is required for any consolatory payment which is over £500… [but] There are some exceptions… Treasury approval is not required if the proposed payment is above £500 but below a limit agreed bilaterally between the department and the Treasury in the context of an independent case examiner (ICE) within the department having made a formal determination of the appropriate level of compensatory payment.” The CPS Board may wish to consider whether discussions should be had with Treasury about the CPS IAC’s payment recommendations.

It is concerning that such a senior staff member does not appear to understand – or has misrepresented – Treasury guidance, and has told the Board that the guidance: “suggests that any payment outside of the delegated level should be novel or contentious. That is not the case here. In my view the IAC has overstepped her TORs in asking the CPS to disregard its own policy in this case. That raises hopes for the complainant and results in internal divergence of views being aired in correspondence with a complainant. That is unsatisfactory. Proper application of the policy would have avoided this situation.”

I did not ask the CPS to “disregard” policy. HM Treasury guidance does not say that any payment outside of the delegated level should be novel or contentious; it says that it is liable to be novel or contentious in most cases. Notwithstanding this, my recommended payment was arguably “contentious” in that the circumstances leading to it were exceptional, and I have rarely (if ever) recommended goodwill payments above £500.

I must reach decisions without fear or favour. Often, my findings coincide with those of the CPS, and a complaint is not upheld. At other times, I find service failure and uphold a complaint. This means having a divergent view: it is the nature of being an independent postholder. It would be "unsatisfactory" if it were otherwise.

I have reported on this in detail because I believe that these actions (and those below) – including the sending of a letter to the Board, of which I had no knowledge or opportunity to challenge – may be seen to be an attempt to undermine, influence or curtail my independence. That would be deeply concerning.

The letter to the Board was in parts misleading and incorrect. It stated that the Civil Litigation Team (CLT) was concerned that the IAC’s practice until recently of recommending compensation for losses suffered in cases where the CPS did not ask for compensation was “fettering our ability to defend legal claims (in short, there is no duty of care in this situation… the losses suffered are as a consequence of the crime not our conduct…”

The implication was that I had been acting inappropriately, yet until recently I could recommend compensation in circumstances where CPS conduct was the cause of the uninsured financial loss, and I did very occasionally recommend such payments in accordance with my terms of reference – but I do not do so now, because the power has been removed. But even if I still had that power, it is not for me as an independent postholder to have my ability to reach fair and impartial judgements fettered by any claims against the CPS that may arise from my evidence-based findings.

It was wrong to claim that they “asked that the [consolatory payments] guidance be updated to tighten up” the difference between goodwill payments and compensation. In fact, I was the one who raised the issue back in 2019, and in subsequent annual reports (due to the CPS’s slow progress in responding to my recommendation).

Mr A’s case illustrates some of the changes, actions and pressures exerted that have eroded my ability to undertake the IAC role in the way that was originally intended.

The First IAC Referral

Mr A’s case was my first IAC referral to the CLT. He experienced poor service (see above) which caused him distress. This was addressed by a goodwill payment of £500 offered by the CPS (albeit that I found the amount to be insufficient in the circumstances).

Previously, I would have recommended compensation to cover some or all of Mr A’s financial loss – as the CPS accepted that he had suffered “uninsured material loss”; Mr A provided clear evidence of financial loss (caused by the defendant); the CPS failed to ask the court to consider making the defendant pay compensation; and the

CPS conceded that it was likely that the court would have made an order for compensation, had the application been made and the details of the claim provided.

Now, where I believe payment for identifiable financial loss directly attributable to the acts or omissions of the CPS is merited, all I can do is make an IAC referral. Within days of my first referral, the CPS wrote a misleading and inaccurate letter to the Board to complain. The CPS DLS said that I had referred Mr A to the CLT “advising him to consider taking legal action against the CPS…” Quite the reverse; I was merely making an IAC referral as per my ToR when I suggested to Mr A that:

“No one can second guess whether compensation would have been awarded, but your losses were never brought to Magistrates’ attention by the prosecutor. As the CPS has admitted forgetting to ask for compensation, one option is to consider making a request for payment for identifiable financial loss directly attributable to the acts or omissions of the CPS.

"I have a new power which I have not used before, where I can make a referral to the Civil Litigation Team (CL) where I believe that compensation should be paid. The CL Team will look at IAC referrals, review the circumstances of the case, and respond to you. Although my referrals do not have the legal status of a ‘letter before claim’ (solicitor’s letter), the CL team will consider what I have to say, and this means that you do not need to go to the trouble and expense of engaging a solicitor at this point (unless you wish to).”

In this case, the CLT (whose role is to protect the CPS from litigation) argued that the CPS was not negligent, on the grounds that the CPS as a general principle does not owe a duty of care to victims of crime. Furthermore, there are no statutory duties on the CPS to compensate victims. It was argued that the Prosecutor’s Pledge is not a legal document, even though it sets out the CPS’s commitment to victims; and the Victims’ Code is not a CPS document, but merely minimum standards guidance for criminal justice agencies to follow and does not create a civil duty of care.

The CLT argued that even if a statutory duty of care could be inferred, it is by no means clear that where the CPS failed to ask for compensation, the full amount sought by a victim would become payable, as the amount awarded is at the discretion of the criminal court. (The CPS had already told the victim that it was likely that the court would have made an order for compensation in this case.)

This first case to be referred to the CLT shows the inadequacy of the new arrangements, leaving the IAC unable to secure justice for complainants. Mr A was the victim of an unprovoked attack that left him with permanent injuries. His attacker pleaded guilty. Mr A did everything required to request modest compensation. The CPS accepted that the court would likely have made an award, but due to CPS error was never asked. I would have recommended compensation, had I still been able to. The CLT’s defensive legalistic approach focusses on protecting the CPS; the IAC takes an ombudsman approach, which is to restore a complainant to the position they would have been in had an error not occurred. I am not hopeful that the IAC referral process can achieve a fair outcome for complainants, if Mr A’s case is typical.

When the senior staff member wrote to the Board, they said of IAC referrals that I initially indicated “that every case of a similar nature would be automatically referred to the CLU [it’s known as the CLT] without further consideration. In doing so, she [the IAC] was effectively suggesting that the complainant take legal action against us, raising expectations that there was a cause of action available and rehearsing the arguments the CPS might deploy in defending any claim. That is inappropriate and, in my opinion, an unprofessional response… I remain concerned however, that we will see every such case responded to in this way.”

I never take a blanket approach to cases: each is considered on its merits, but all cases where I would have previously recommended compensation will of course, quite rightly, be referred to the CLT as per my ToR. That is the purpose of an IAC referral. It is neither “inappropriate” nor “unprofessional”; it is, however, a way of averting legal action – quite the reverse of what was claimed. I am pleased that the CPS Board Chair disassociated the Board from the views expressed in the letter, and that support is important if the independence of the IAC is to be safeguarded.

Independence of the IAC

My observation over the last three years, and this reporting year in particular, is that the CPS appears to have eroded the IAC role and undermined the postholder. For example, my discussions with the CPS to find a fair resolution for Mr A have been presented as “the IAC was persuaded to tone down the letter”. If the CPS’s purpose in meeting to discuss difficult cases is to exert pressure to change the tone of my determinations – rather than, quite appropriately, to challenge the facts or understand each other’s thinking – that is inappropriate.

In particular, it is concerning that the CPS object to internal, complaint correspondence being quoted in my determinations, as it is standard practice in most (if not all) independent complaints review functions, to quote from relevant correspondence. It enables complainants to understand what happened in their case. The CPS view is that it: “opens our staff up to scrutiny and it could also be problematic if we are to defend a civil claim in the future since it could be seen as an admission of liability. I appreciate the need to respect the IACs independent boundaries, but I remain concerned at this approach. I will be advising all CPS Areas to only refer the key documents to the IAC in future to prevent this happening again.”

Such instruction to CPS areas would have had an adverse effect on my ability to get to the truth of what happened in cases, and would have undermined public trust and confidence in the CPS, although I have been assured that this action was not taken.

One important aspect of my own accountability is this annual report, which is rightly scrutinised by the Board, and I make myself available to answer questions on its content and my own performance. My ToR state that I must report here on cases where a recommendation has been rejected, such as that of Mr A. This year, the CPS took issue with that, stating: “You will see that in this complaint, the IAC has referred to the fact that she will highlight this issue in her next Annual Report. You will also see the most recent Annual Report traversed a number of internal discussions which led to the updating of the Goodwill payment guidance. We must be able to have a frank exchange of views without it being shared in correspondence with complainants or the world at large in a published Report.”

Even if I were not required to highlight cases such as Mr A’s, the issues arising from such complaints are worthy of discussion in their own right. The IAC role is not statutory, and the IAC has very few powers. The postholder has no delegated decision-making with financial authority up to a certain limit, and cannot any longer even simply recommend compensation, let alone require it. The only leverage available is through relationships with the independent Board, and the vehicle of the annual report. It is right that concerns are shared with wider stakeholders in this way, and it is what complainants expect, as can be seen from the following quote:

“We have no hesitation in agreeing to the inclusion of this matter in your annual report and believe that it is important that these issues are discussed if there is to be any prospect of lessons being learned from our experience.”

PHSO referrals in 2023/24

This year the PHSO received 19 complaints about the CPS which were all concluded without an assessment. None were accepted for detailed investigation. One outstanding CPS case accepted for detailed investigation in a previous financial year was concluded and not upheld in 2023-24.

Visits

Due to volume of work, I made just one in-person visit this year to Newcastle (CPS North East). It was useful to meet with both new and experienced lawyers whose role includes drafting complaints responses.

Case complexity and follow-up

Yet again, case complexity continues to be a significant feature. Case files are bigger, and cases take longer to get to grips with as a result. Some complaints during the year date back over several years, or they incorporate interconnected complaints – all adding to complexity and time.

Follow-up correspondence also continues to take a disproportionate amount of time. Complainants dissatisfied with the outcome of their determination seek to reopen it, challenge it, or to ask further questions.

Borderline cases have also taken time, as rejecting a case that may have minor service elements but is primarily about a legal matter, requires significant reading in order to assess and then reject. All of the above takes away time from new casework and creates longer waits for complainants. This year I have discussed with Private Office thoughts on how some of this growing aspect of the role may be managed going forward – possibly by an enhanced IAC assistant role – but this is work in progress.

3. Caseload Comparisons and Performance

Complaints received

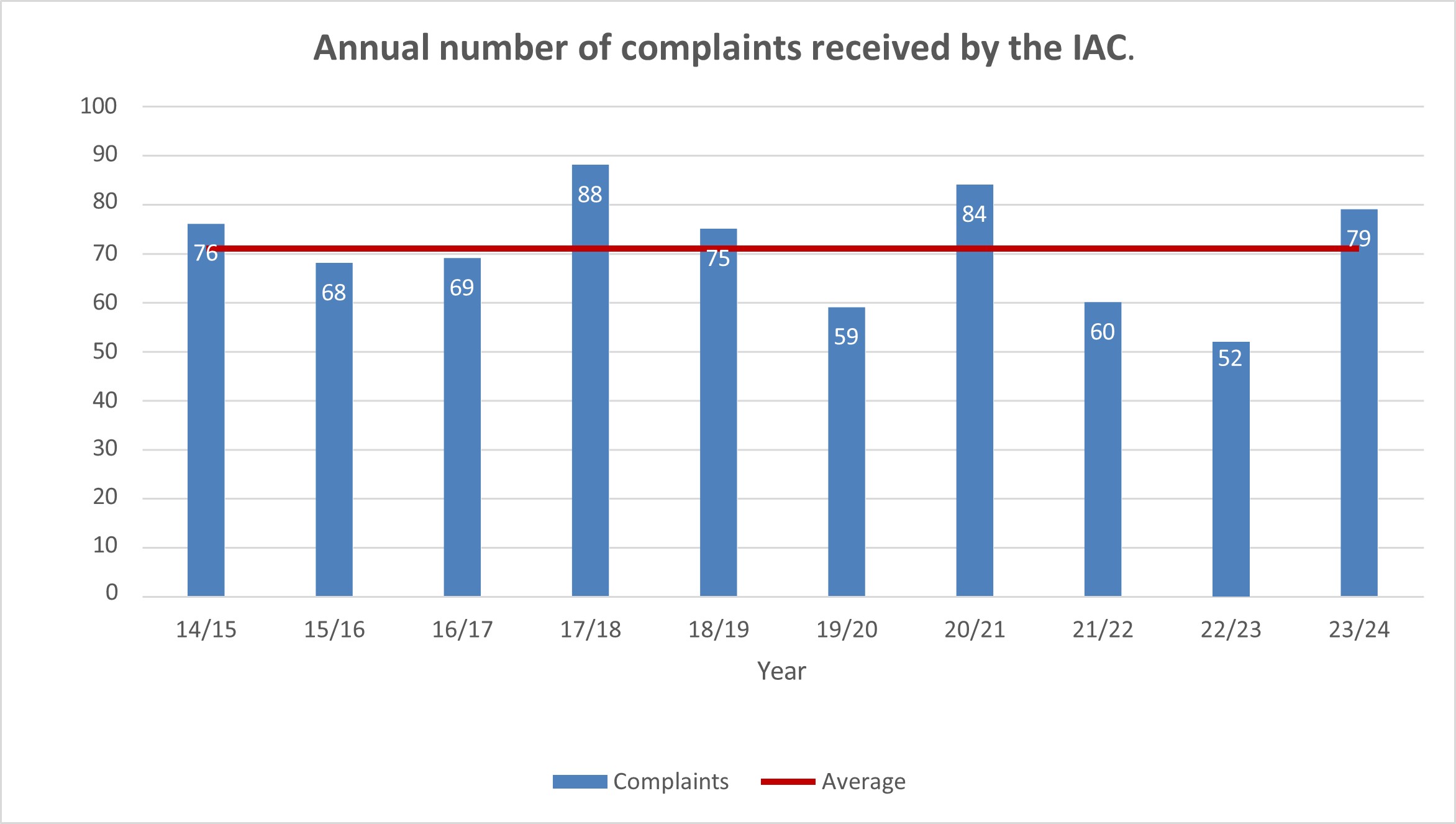

The number of complaints received by the IAC’s office has risen sharply, from 52 in 2022/23 to 79 this financial year – making this the third busiest year ever. It is not possible to say why this is: complaint escalations to the IAC have never followed any pattern. Of those 79 cases, 39 were accepted in-year (compared with 36 last year) and 15 cases were rejected.

Of the 39 cases accepted during the year, by the year-end:

- 12 had been completed and dispatched (a further 18 cases received the previous year were also dispatched – so a total of 30 cases were sent out during the year);

- 2 were in the process of being reviewed by the IAC;

- 25 cases were still awaiting assessment at the year-end.

The data below shows the number of complaints received by the IAC.

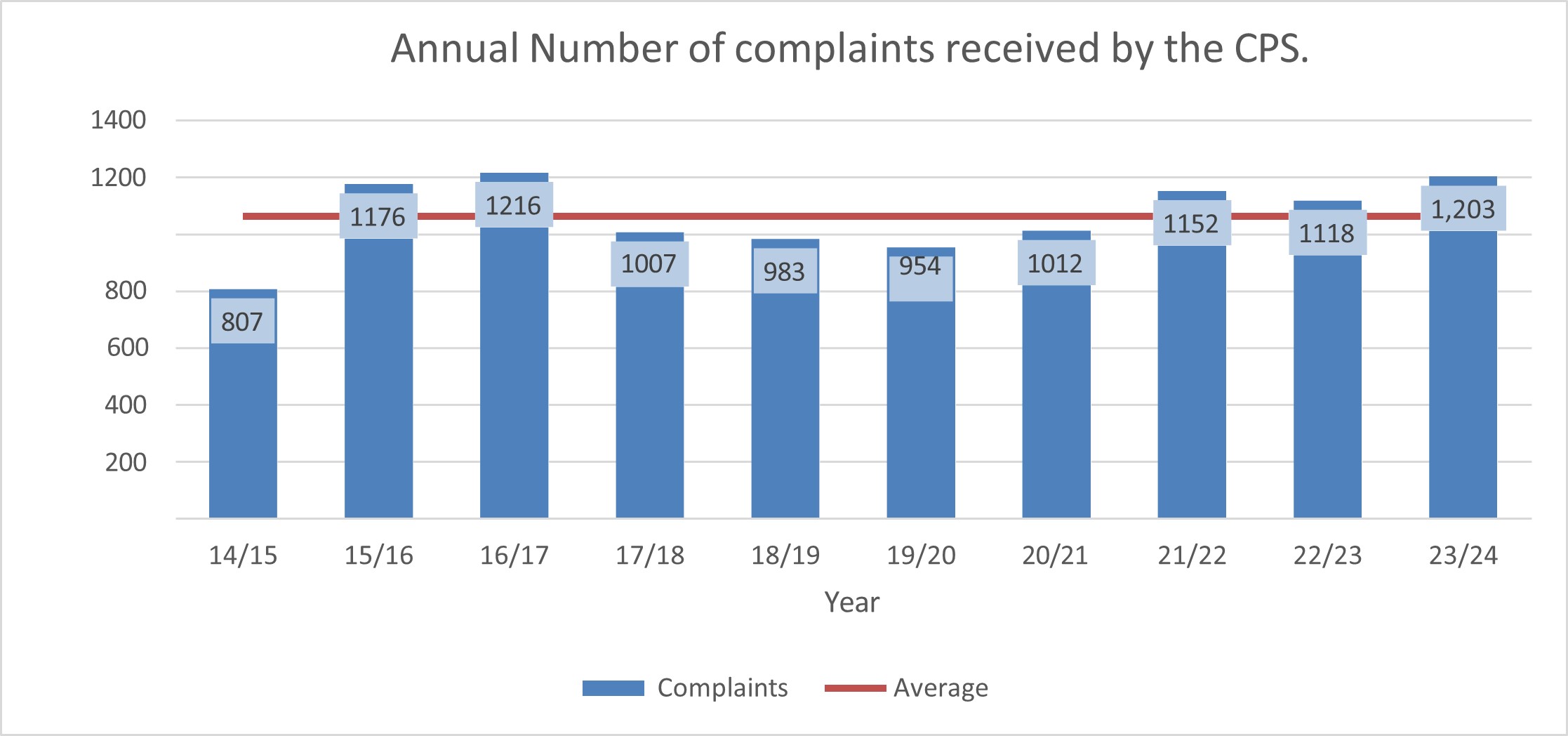

The CPS complaints data below shows the number of complaints received by the CPS.

Complaints rejected

The IAC rejected a total of 15 cases this year, for the following reasons:

- 9 were wholly or primarily concerned with legal matters so were rejected as not falling within the IAC’s remit.

- 3 cases were rejected for reasons of proportionality, in line with my terms of reference. They contained only minor service elements, or issues had already been addressed by the CPS.

- 2 cases were rejected for reasons of both proportionality and being primarily concerned with legal matters.

- 1 case dated from before 2013 and was rejected due to being out of time.

Accepted, completed or ongoing during 2023/24

The situation at the year-end (31 March 2024) was as follows (note that this includes cases that may have arrived the previous 2022/23 year):

- 30 had been fully reviewed and the final determination report had been sent to the complainant (12 received in-year and 18 received prior to 1 April 2023 and carried over)

- 1 was completed but awaiting final checks before being dispatched.

- 1 was with the IAC but still in draft form.

- 7 had completed formal assessment and were accepted as valid for an independent review, but had not as yet been formally accepted by the IAC. (Effectively, these were now in the ‘waiting list’ and will be carried into 2023/24.)

Performance and waiting times

Of the cases closed in 2023-24, 28 were completed within the 40 working day target, when calculated according to the original method (with the clock starting only when a complaint is formally accepted by the IAC.) Two cases were overdue, as a result of extended discussions with the CPS about disputed recommendations.

As this measurement has never reflected actual waiting times, since last year I have been measuring from the point at which the file is ready for the IAC, not from the (later) date when the IAC requests it. This provides greater transparency and better reflects actual waiting times from the date on which the case file is ready for review.

- The average wait is 91.6 working days.

- 5 cases were completed within the 40-day target, using the real measure.

- The shortest wait from the file being ready for the IAC, to a case being completed by the IAC, was just 7 days, and the next shortest was 9 days.

- The longest wait was 156 working days.

Complainants are understandably unhappy about the length of wait for their complaint to be reviewed, which is on average more than twice as long as the target. Unfortunately, there is little that can be done to improve turnaround time unless the time commitment is significantly increased, which would be hard to justify, and/or the threshold for review is raised.

I would be concerned to see a raised threshold, as there is already a rigorous process of rejection in place, as demonstrated by the 15 rejections during the year. Cases should only be rejected if they do not meet the criteria, but in order to ensure that a case is rejected for the right reasons, a time-consuming process is involved in which case papers have to be read and assessed: sometimes a rejection takes almost as much time as a full review.

Who complained?

Of the cases completed in 2023/24, 24 complainants were victims or the relatives or representatives of victims, and 6 were defendants or those who had been considered for prosecution.

Outcomes

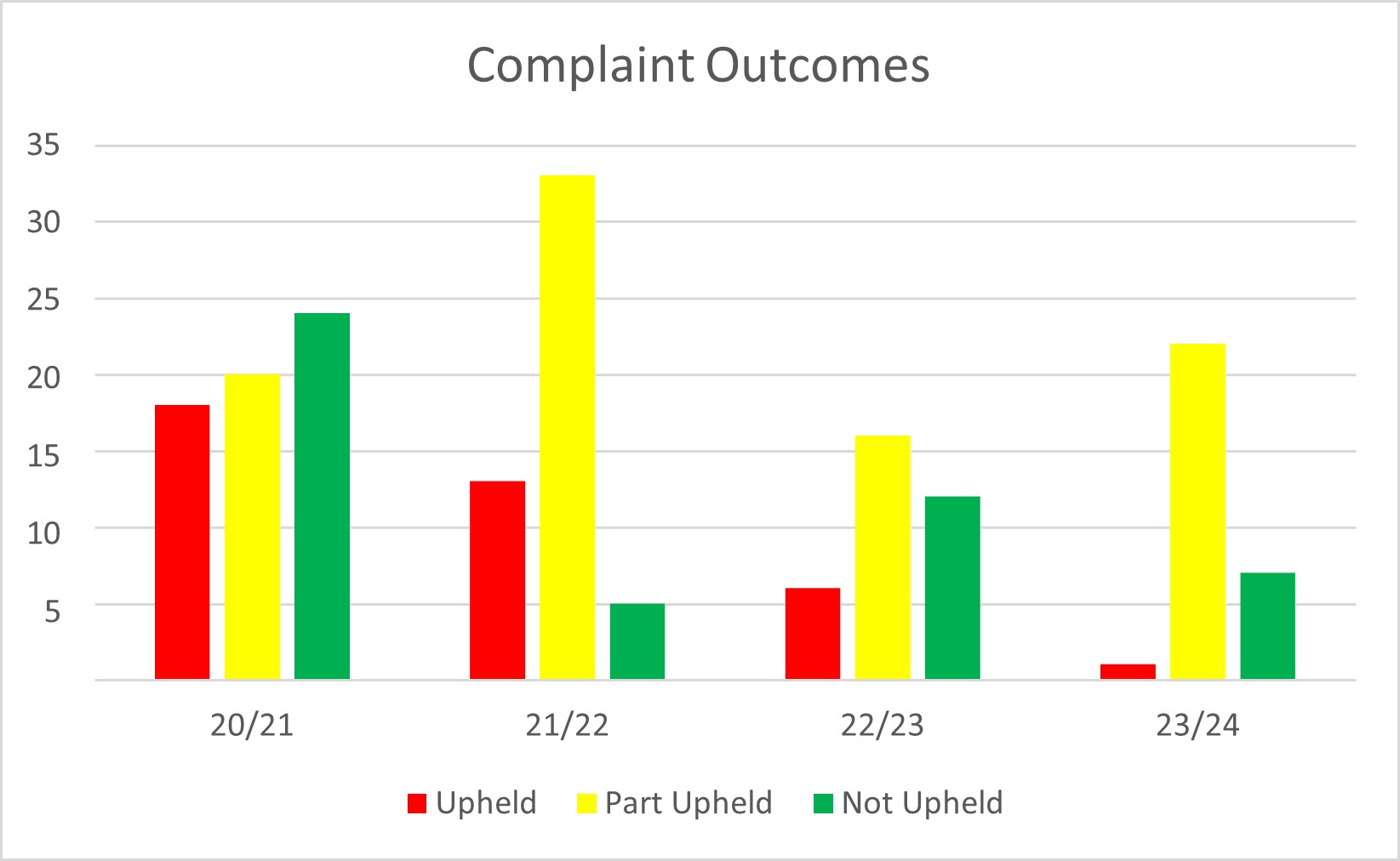

The table below shows the outcome of the reviews completed each year over the last four years.

Recommendations

I made recommendations in 15 cases (some cases contained multiple recommendations); 10 involved some sort of payment; and in 7 of the cases, I asked the CPS to provide further information or an explanation to the complainant and/or an apology.

4. Reasons for complaint and resolution: Real life examples

Sadly, the same avoidable errors are complained about year after year. Here are some examples from this year, to highlight the impact on individuals. It is too easy to dismiss or excuse service failures as mere unintentional breaches of policy, procedure or protocol, while forgetting the real human suffering that can flow from a simple mistake.

Failure to ask for Compensation

I have repeatedly brought to the CPS’s attention that many cases involve the failure to ask the court for compensation. Mr A’s case illustrates only too well the impact of this failure on individual victims of crime. He found himself unable even to afford a prescription, and his broken tooth repair fell out and he did not have the money to replace it. He would likely not have been in that position had compensation been sought, as was his right. The organisation responsible for failing to ask for it then refused him any compensation, even after admitting fault. It’s bad enough being a victim of crime, without then having to face financial hardship because of another organisation’s failure.

Failure to ask for a Restraining Order

I partly upheld Ms B’s complaint. She and the defendant were in a relationship when she reported sexual offences and assault. He pleaded guilty to some of the offences, was acquitted on others, and received a prison sentence.

Following the trial, Ms B’s Independent Domestic Violence Advisor (IDVA) was concerned that an application for a Restraining Order (RO) had not been made. She said that Ms B and her three children had been left in “danger”. It appears that the police were supportive of an RO, as the IDVA later wrote about how Ms B had been identified as a victim of domestic abuse and was “at risk of significant harm or homicide” and that concerns were so significant that the police were undertaking weekly check-ins since the trial and a security assessment of her home had been completed. The CPS lawyer tried to get the case listed for a retrospective application, but the court did not consider this to be possible and refused the application.

Ms B complained to the CPS. This aspect of the complaint was upheld and she received an unreserved apology, but the CPS said all options for a retrospective RO via the Criminal Courts had been exhausted. She then wrote to me, explaining that this failure had created significant stress and worry.

When I investigated what had gone wrong, it was unclear from the available information whether the police identified that an RO was needed, but failed to inform the CPS; or did request one, but the CPS lost it. Regardless, the CPS reviewing lawyer accepted that she should have drafted an application for an RO, and was also of the view that the barrister should have advised that an application be submitted.

Both the lawyer and barrister received feedback, but that did not remedy the matter for Ms B.

Ms B told me that the failure to ask for a Restraining Order had had an “astronomical” impact on her mental health and had made her PTSD worse than ever. She said: “I am struggling to get through each day currently due to the stress, distress and immense sense of fear I feel on a daily basis. I am on edge constantly, panicking when people come near my house (even though I have cameras), cannot go out of the house and always have to have someone with me. I have flashbacks everyday, caused by numerous triggers (some which are unavoidable on a daily basis) and feel like this is a ticking time bomb waiting to go off, as it will sooner or later. I am not living my life, I am just existing day by day, and it is hugely effected by this incident. The RO would have given us guaranteed protection for a substantial amount of years; allowing us to safely move on with our lives, be happy and plan the future and life that we deserve. Whereas now, I am stuck in limbo again, not knowing what to do or what will happen and in exactly the same position that I was nearly 3 years ago when this whole process started. I am unable to put this whole experience behind me and allow myself the time and ability to piece my life back together again, as it has been completely and utterly destroyed. Even though we have the Non-Mol [non-molestation order, a Civil law Restraining Order] order in place, I will have to apply for the order yearly, reliving the stress of having to go back to court and through the painful and distressing process yet again, each year, with no guarantee that it would be approved. Which would leave us vulnerable yet again.”

Ms B felt that aside from an investigation to establish what had gone wrong, she wanted a goodwill payment to acknowledge the CPS’s error. I agreed. These were serious allegations which resulted in two guilty pleas, and Ms B now faces the worry and inconvenience of having to make annual applications for a non-molestation order. It is clear from Ms B’s story that forgetting to ask for an RO is more than a mere administrative oversight: it can adversely affect people in deeply distressing ways, leaving them feeling worried, vulnerable and at risk.

You can read more about the impact of the failure to ask for a restraining order in the case highlighted in the ‘Complainants’ Voices’ section.

Poor Communication

Baby C was born in 1997, having been delivered by an Obstetrician Senior Registrar. Sadly, he died a short time after his birth, and the coroner found this to be due to massive intracranial haemorrhage following a traumatic forceps delivery. The Obstetrician’s employment at the hospital came to an end shortly afterwards, and he left to work abroad some months later, having been unable to secure work in the UK. The coroner referred the matter to the police for investigation, and the NHS Trust referred the Obstetrician to his regulatory body. As the Obstetrician had left the UK, he was never interviewed by the police. In 1998, the CPS concluded that there was insufficient evidence to charge the Obstetrician, but in 1999, took a decision to charge. A warrant of first instance was issued in 2000 for the alleged offence of manslaughter.

In 2019, the police contacted the CPS about what should happen with the warrant that had now been outstanding for 19 years. The CPS undertook a fresh review, as there was contradictory medical expert evidence and the law relating to gross negligence manslaughter had changed over the intervening years. Thereafter, it was decided that there was not a realistic prospect of conviction for gross negligence manslaughter, and that the warrant for arrest should be withdrawn.

Baby C’s mother and father were unaware this had been returned to the CPS in 2019. When they were told, various events occurred which culminated in a complaint about areas of the handling of this matter. In 2023, they escalated the matter to my office. I will highlight just one aspect of the complaint here: the manner in which the review decision was communicated.

The parents wrote to me that it happened “in an unscheduled meeting at our home when only one of us was present. This, in itself, had several regrettable consequences which impacted both of us and our children… Had we been informed, as we should have been, at the outset of the review this would have been avoided either entirely or significantly.” The CPS responded that following the approach from the police, it was decided to review the file based on the evidence used to make the initial charging decision. At that stage, a decision had not been reached and, given the potential for the case to continue, “it was decided not to inform the family of the review given the age of the case and the impact this may have on them after so much time.” The CPS’s actions were well-intentioned, but I believe the wrong judgement was made. With hindsight, the CPS accepted that “a more sensitive and bespoke approach should have been taken”, and that there had been a failure in communication and a lack of empathy which had caused anguish. It was also accepted that contact should have been made prior to the decision being made.

I found that consideration was given to how this decision would be communicated, and it was decided that the police Family Liaison Officer (FLO) would make a home visit with a letter of explanation from the CPS. My investigation found that although the FLO went to the family to inform the parents, a detailed letter explaining the decision was not emailed until the following day. I was concerned that having been given such devastating news orally and out of the blue, there was no letter ready for them to reread and digest in their own time over the rest of the day.

Unfortunately, the failure to even notify Baby C’s parents of the review meant that any decision would come out of the blue, and the negative effect of undoing a decision made two decades ago could have been anticipated. To these parents, this was not an administrative task to review a longstanding warrant: rather, it was an event that abruptly brought to a halt their efforts to obtain justice for the loss of their baby.

Above, I have highlighted just three stories, but there are real people impacted by all of the following consistent themes:

- Administrative errors: such as the wrong date for a court hearing being provided to a witness, or a document being placed in the wrong file.

- Case management: there have been cases which were not actively managed, such as when the CPS has not chased the police for overdue or missing information, or failed to escalate within the police when action plans became overdue. This can result in the discontinuance of a trial.

- Last minute review/preparation: this remains central to many complaints. In these complaints, case files are often reviewed too close to the court date, typically the day before, when it can be too late to secure missing information. This may mean that a trial has to be adjourned, or a prosecution dropped altogether, leaving victims feeling that justice has not been done.

- Agent prosecutors: they continue to feature in complaints cases. Perhaps because they are external to the CPS, they are less familiar with its policies (despite receiving training).

- Victim Personal Statements (VPSs): the failure to offer the victim an opportunity to read out their VPS is not only a breach of the Victims’ Code: it causes distress to those wanting the defendant and the court to understand how they have been affected by a crime. This can be very cathartic for victims, and some believe that the outcome would have been different if only the court had understood the full impact of the crime on them.

- Missing, incomplete or inadequate Hearing Record Sheets (HRSs): the HRS is the CPS’s record of what happened at court. It is a vital document if there is a complaint. Sometimes the HRS is missing, or lacking in sufficient detail. For example, it does not always record whether compensation was asked for; what the reasons were for magistrates refusing an adjournment; or what instructions were given in phone calls to the CPS.

- Behaviour at court: Sometimes victims complain about poor communication at court, insufficient time with prosecution counsel, or insensitivity and brusqueness (often involving agent prosecutors).

Consolatory or ‘goodwill’ payments

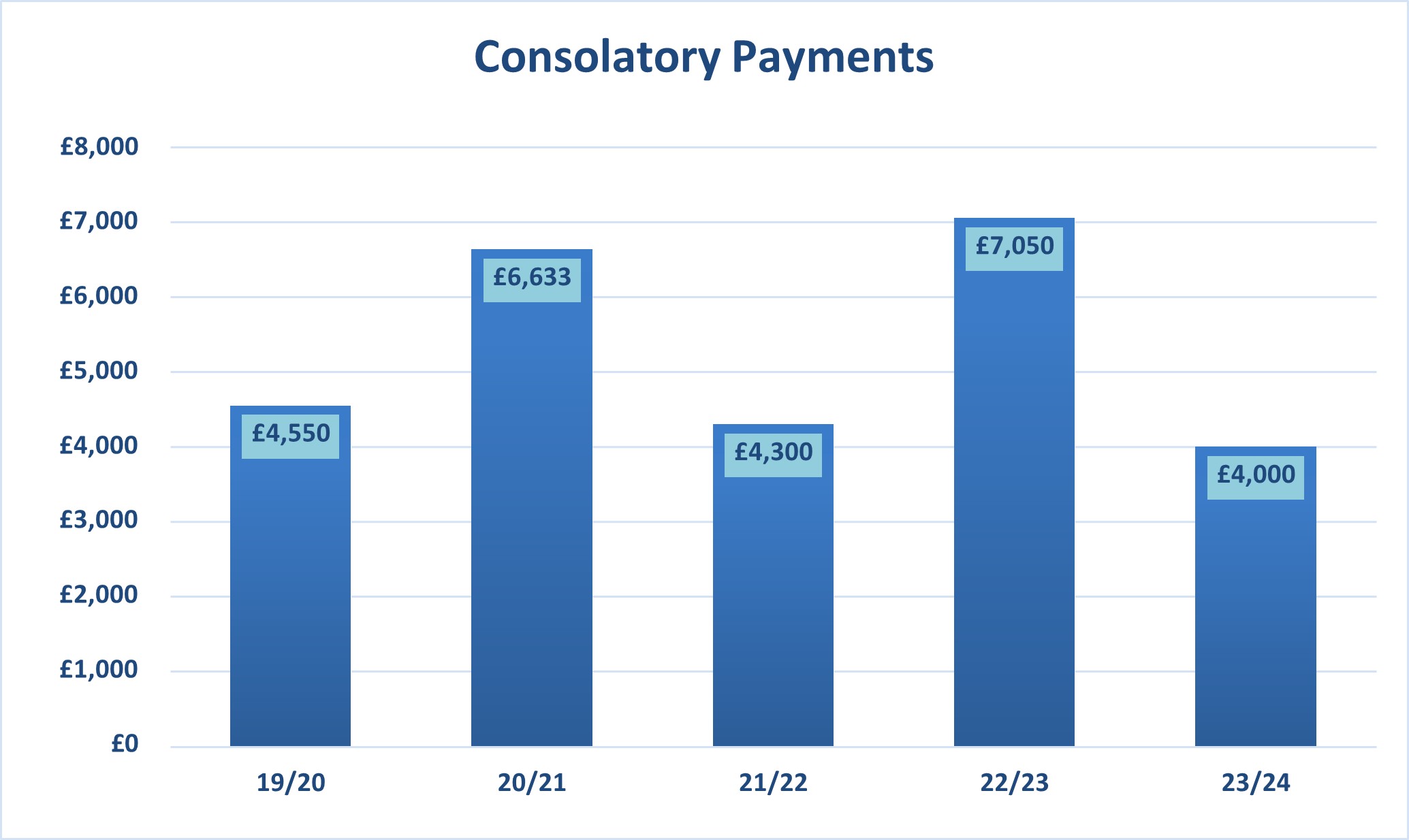

During 2023-24, I recommended 10 payments. The lowest was £100, and the highest was £500. Sometimes, a consolatory payment has already been offered before a case reaches the IAC. Unless the amount is so low as to be unreasonable, as in the case of Mr A, the IAC will not substitute a larger sum. In Mr A’s case, my recommendation for £250 on top of the £500 the CPS had already offered, was rejected. The total amount recommended by the IAC came to £4,000 in 2023/24, (which excludes the £250 recommended for Mr A, as the CPS did not agree to pay that). This compares with £7,050 the previous year.

5. Complainants’ Voices this Year

Research has shown that complainants whose cases are upheld usually go away happy, and those whose complaints are not upheld express dissatisfaction when surveyed, regardless of the level of service provided. It is therefore especially heartening to receive positive comments from those whose complaints were not upheld – such as the following sad case, involving the murder of the complainant’s mother. Although the complaint was not upheld, the complainant found comfort in knowing that her complaint had made a difference for others.

…I am glad that at least some accountability has been taken for the family bereavement service failings and am grateful for that at least. It also calms me somewhat to know that some learning has come from this and I do hope that it prevents other families from having to go through what mine have in future.

Often a complainant is not interested in receiving a financial payment; rather, they just want someone to listen and understand. In the following case, one of coercive and controlling behaviour, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. A Restraining Order was not sought as counsel had been told by the police that the previous order was still in place. (In fact, the Restraining Order had expired, and this was contained in counsel’s file for the pre-trial hearing and the complainant had discussed concerns in relation to the expiry of the Restraining Order with counsel at the first trial.) I partly upheld the complaint. Afterwards, I learned of the positive impact of an empathetic response, even when a complaint is not fully upheld.

“You don’t even know me as a person but you recognised and understood in a way others haven’t and I wanted to say the biggest thank you for acknowledging what had happened to me, instead of just another victim. It’s humans like you that stand for change, listen and acknowledge. I hope you are recognised for all you do.

"I never wanted money or compensation I just wanted someone to understand and to see there was serious faults in this case. I felt completely let down by the process Moi and I found waiting years to attend court again the most traumatic experience...

"All I wanted was a restraining order in place and still until this date I don’t have anything , thank you for recognising how scared I must of felt that weekend and going forward . I felt like I had just been (dumped) so to speak by the police. That they just closed the door on me and I was just another number .

"This time In my life impacted not only me, my career, but mostly my mental health but you relieved some of this .

Thank you for being you Moi”

In so many cases, complainants are grateful for a thorough review – even where their complaint is only upheld in part, as in this case. A young man had been riding his motorcycle when it collided with a van, and he was pronounced dead at the scene. The driver was charged with causing death by careless/inconsiderate driving, and he pleaded guilty at the first hearing. The victim’s parents had concerns about the conduct of prosecution counsel at the sentencing hearing, but found some comfort in knowing that a detailed investigation into their complaint had been carried out:

“Thank you very much for your extremely detailed investigation and response to our complaint… [our son] did not receive the justice he deserved. Once again our sincere thanks to you for your kind consideration of our accusation.”

Complaints are often frustrated by the limitations of IAC investigations, as these complainants pointed out:

“[We] are grateful to you for your attention to detail. We are pleased that this will be brought to the attention of the DPP and the inclusion in your report of the impact on us of the re-opening of this case and the way in which it has been handled is something we welcome. We understand that your jurisdiction does not allow you to form a judgment on all of the matters we have raised…

"The only point that we would like to make is that we would not want it to be suggested that the process of making a complaint to the IAC’s office has provided us with a complete resolution of all the matters that have concerned us with regard the CPS handling of [our] case. This is not criticism of you at all, but a reflection of the fact that the IAC’s role is to address service and not legal complaints.

"Many of the matters that we have raised fall under the heading of complaints about the legal decisions made in the VRR process. We do not believe that these will ever be properly addressed as it seems that review of legal decision making is not subject to any kind of external, independent review and there is no other way that the system allows us to pursue these matters.

"… we are grateful to you for the care with which you handled this matter. We are sure we are not alone in thinking that an independent review of how a case has been handled can go a long way to repair the damage that may have been done. The absence of such a person to turn to would be a great loss to those who have had a negative experience.”

Moi Ali

Independent Assessor of Complaints

July 2024

Annex: IAC’s Terms of Reference

The IAC's Terms of Reference can be found on the main IAC page on the CPS website.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to the former Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) Sir Max Hill KC, for reading every report I write – and to his successor, Stephen Parkinson, for continuing the tradition. As I have said before, that level of genuine interest from the very top is appreciated. I am grateful to both for making time to see me during the year.

I am always grateful to my assistant, without whom I could not undertake this role. My outgoing assistant, Tony Pates, has been there to provide support since my first day as IAC and he is sadly missed, having semi-retired in the summer of 2023. He has been ably replaced by Lauren Fensome, who has already settled into the role and is juggling a heavy workload, and I am lucky to still have occasional support from Tony as well. I must not overlook the support of Mercy Kettle over the years, for supporting the IAC office with calm professionalism.

Thanks also to Harvey Palmer in Private Office for ensuring that the IAC is consulted as appropriate and provided with sufficient support to undertake the role. And to the CPS Board, and the Chair in particular, for support in dealing with some challenging issues during the year.

Finally, thank you to CPS areas for their support in enabling me to undertake investigations into their work, and for a good working relationship at local area level.

Moi Ali,

July 2024